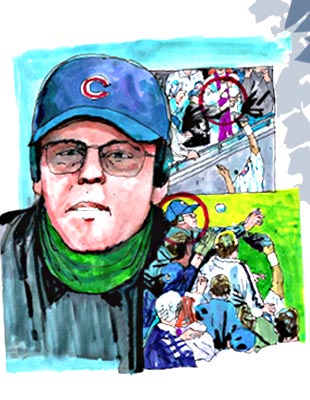

It's impossible not to imagine all of it -- Alou, the ball and the dreams of every Cub fan -- coming together right above my head. And it's frightening to realize this: I likely would have done the same thing. I would have been Steve Bartman.

I

t's a steamy, hot Chicago afternoon, and deep inside my own personal heaven I am searching for hell.

The Steve Bartman seat.

I'm on a quest to find sports' most infamous fan. My goal is to peel back the layers of the mystery behind Bartman, who hasn't provided any insight into the most painful night in Chicago Cubs history -- October 14, 2003 -- other than a 185-word statement the morning after. I desperately want to understand more, and I'm starting at the scene of the crime: Wrigley Field's left-field corner just beyond the foul line.

Aisle 4, row 8, seat 113.

A nearby usher sends me in the right direction, motioning to the last seat in the eighth row, the one with the Cubs stickers plastered across it. The forest-green color stands out on this sunny day, and I instantly wonder why it isn't black, a memorial-like armband forever symbolizing the death of a World Series dream.

The team still sells this seat for every game, the usher tells me, but on this day, whoever bought the front-row seat with the unobstructed view of left field has yet to show up.

So I sit.

My toes are close enough to push against the back of Wrigley's famous brick wall. My eyes close enough to pinpoint which blades of grass were stepped on during batting practice. But Wrigley Field -- the happiest place on earth for any Cubs fan -- has in my mind quickly turned dark. I can't help but lean forward, look to the ground and picture Moises Alou on that chilly autumn evening. I can't help but look toward home plate, then to the clear blue skies above and picture a lazy fly ball heading in my direction.

It's impossible not to imagine all of it -- Alou, the ball and the dreams of every Cubs fan across the world five outs away from the World Series -- coming together right above my head. And it's frightening to realize this: I likely would have done the same thing.

I would have been Steve Bartman.

A pair of jersey-wearing Cubs fans behind me, guys in their 20s who bought their tickets on eBay and are ditching work for the day, ask what I'm up to. I tell them it's the Bartman seat. And they react like third graders who have just been given extra recess: complete giddiness.

"You're kidding me!" Jim Laubinger says, nearly spilling his full beer as he leans in to get closer to the seat. "Can I sit there for an inning?"

Seconds after I give him permission, his buddy Jason Eardley chirps up, "I get it next inning!"

Ten minutes later, the Red Sox fans behind us chime in. They want to know what we're buzzing about. "Are you kidding?" Eardley says. "This is the Bartman seat." Now they want to sit in it. Before we know it, it seems like half the section is rotating in and out of the seat before innings, after innings, during innings. It's like a line waiting to sit on Santa's lap. Only this lap is the most horrific plot of real estate for any Cubs fan.

A college-aged woman announces to the section that she's going to get a beer. But she'll be right back. "Bring us one," Eardley says. "I mean, we showed you the Bartman seat."

She smiles and flirts, but returns empty-handed. The message, however, is clear: Two years later, people still care about Bartman. The pain is still there. This simple spot is a piece of molded plastic that will forever belong to everyone who has loved the Cubs. Me. My wife. My dad. My grandfather. My best friend. Everyone.

They're the reason I'm here. They're the reason I must get answers. Whatever happened to Bartman? What became of the man whose bare hands got in the way of the most notorious foul ball in baseball history? Some said he'd moved to London or Florida. Others murmured that he'd undergone plastic surgery, hair replacement, name changes. Was any of it true?

"He's doing well now. He's fine. He leads a normal life, as far as I know. Every so often, I see him head into the house, I wave, ask how he's doing and he always smiles back."

-- Neighbor Ron Cohen

"Whether he wants to admit it or not, that one play may have changed the course of baseball history. I was sick when I watched that happen. Absolutely sick to my stomach. But I still want to know what happened to him."

-- Crisis management expert Jeff Lashey

Bartman, 27, has never said a word beyond the statement. He has vanished from the public eye, like a perfectly executed trip into the witness-protection program. Is he still a Cubs fan? Is he married? How has he dealt with having his name associated with the biggest failure in his favorite team's dubious baseball history?

I wanted to know. Deep down, every Cubs fan wants to know. This is why I'm in Chicago.

The research begins

I start by throwing Bartman's name into Google, which is putting a cramp into the business of private investigators everywhere. The results are sickening. "Death to Steve Bartman" message boards. Blogs that encourage Cubs fans to, "not let him do this to us" and to "seek revenge."

Then there are the doctored photos. Bartman hiding in Saddam Hussein's bunker. Bartman pushing the button that set off the World Trade Center bombings. Bartman holding a match to the Hindenburg explosion. And a mug shot with Bartman as the lead suspect in the Washington, D.C., sniper shootings.

There are T-shirts: "Sit Down Steve." "The Curse Lives -- Thanks Steve." And, "Cub fan Rule No. 1: Keep both hands on your Old Style."

And then this shirt, mocking the MasterCard "priceless" commercials:

- Tickets to Cubs game: $200

- Chicago Cubs hat: $20

- 1987 Walkman: $10

- F-----g up your team's chances of winning the World Series: Priceless

Does anybody care?

Close your eyes and picture life as Steve Bartman.

Imagine the Cubs being the core of your existence and having your name and photo right alongside the billy goats and black cats of past Cubs failures. Imagine the realization you likely will never visit Wrigley Field again. Your eyes will never gaze upon the dark green ivy, bright green scoreboard or muted brown bricks. Imagine turning on a random St. Louis Cardinals game, watching Albert Pujols chase a foul ball into the front row at Busch Stadium and listening as it sparks a 10-minute conversation about you. It's enough to prompt a swoon into a lifetime of unspeakable depression.

To better understand the pain, I call the psychology departments at Northwestern and the University of Chicago. They don't seem interested in local problems, so I enlist the help of Dr. Richard Lustberg, a New York-based sports psychologist who has worked with everyone from Little Leaguers to major leaguers in his 30 years practicing and studying sports psychology.

Lustberg has never met with Bartman, never spoken with him. But he insists he can help me. His ego is immense. He tells me that if ESPN flies him to Chicago, he can convince Bartman to join us on a trip to Wrigley Field. I tell him he's nuts.

"It's what I do for a living," Lustberg explains. "I get people to talk. Just give me a shot."

I politely decline, but press him for insight into Bartman's head. The way Lustberg talks, with his authoritative, non-stop psychobabble, he sounds like he has the entire situation figured out.

"He simply loved the Cubs too much," Lustberg takes 15 minutes of premium couch time to explain. "That's why it hurts."

I argue that it's impossible. That if Bartman loves the Cubs too much, then I love the Cubs too much.

"That's why you think this is such a big deal," Lustberg said. "But in the grand scheme of things, it isn't. Nobody cares. And that's what I would try to tell Steve."

Preposterous. Clearly, the lifelong New Yorker doesn't get Chicago sports. Bartman's blunder is one of the biggest sports stories in the Windy City's modern sports history. Jordan's six championships, Super Bowl XX, Sosa's Summer of '98 and Bartman. But Lustberg doesn't budge. He challenges me to ask 100 random Chicagoans -- white, black, young, old -- if the name Steve Bartman means anything to them. He contends less than half of the city will recognize the name.

I laugh again, hang up the phone and head to Blues Fest, a melting pot of Chicago's multicultural diversity in Grant Park. On this humid, overcast Sunday, the park is filled with more than 100,000 people. I talk to everyone from homeless men begging for change to the economically elite sipping on wine and nibbling on cheese. I talk to police officers, preachers, garbage men, yuppies, even four Indian women sitting on a park bench bobbing their heads to the blues.

I ask every single one of them, 100 people total: "Does the name Steve Bartman mean anything to you?"

Twenty-seven say yes. Seventy-three say no. One "no" is a guy wailing on a harmonica in a tattered Cubs hat. When I clue him in that Bartman has something to do with the Cubs, he still can't guess.

"I just wear the hat," he says.

Cracking the code of silence

Lustberg had helped me, but in the wrong way. His argument was that nobody cared. I argue Cubs fans care. Plus, I care immensely, and that burden must be eased.

I soldier on and put in a call to Jeff Lashey, an executive vice president and crisis management expert at Edelman, one of the world's top public relations firms. PR agencies usually are the enemy in stories such as this, always looking to place things in a positive spin. Good PR is about staying on message, but with Bartman the message is doom.

So I go straight for the jugular, seeking to learn how they would advise Bartman if he hired them.

Lashey is downright energized about my call, a break from the monotony of helping Fortune 500 companies overcome PR disasters. He begins by analyzing Bartman's statement.

According to the expert, the message was flawless.

"It was very personal, with his own real feelings and emotions in it," Lashey said. "And that's an effective way to deliver your message. He did it right."

So right, that Lashey says Bartman has every right to not talk to me. Or anyone else for that matter.

"It depends how much he wants to bleed his heart," Lashey said. "If he feels he needs to further convey what this has all been like for him, then maybe I would say do a select interview. If he's still struggling with how he's going to live his life and this is just going to re-ignite the pain, then maybe you don't go that route."

But in this day and age, everybody talks. From victims of child abuse to mistresses of convicted murderers, everyone ends up telling their stories to "Dateline," or "20/20" or "Entertainment Tonight."

With offers from media outlets across the nation, why would Bartman be any different? We're approaching the two-year mark. Surely, it's time for his story to be told.

Lashey, a former television reporter, can't keep the instincts from his previous job from kicking in. In one sentence he blows up the argument from the shrink and further fuels the fire that people still care.

"If I were a sportswriter, I'd do what I could to get him to talk to me," Lashey said. "Because whether he wants to admit it or not, that one play may have changed the course of baseball history.

"I was sick when I watched that happen. Absolutely sick to my stomach. But I still want to know what happened to him."

The Stakeout

I need to find Bartman. See him. Know if he's doing as well as his neighbor suggests. So, I head to his parents' home in Chicago's comfortable north suburbs. Although many offspring leave the nest as they close in on their 30s, I have pieced together the fact Bartman currently lives at home.

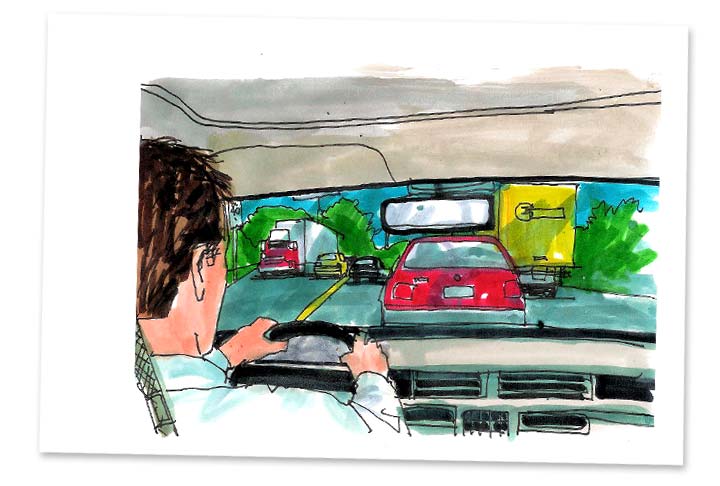

The address is easy to find -- it's still plastered all over the Internet. So armed with the facts and just the facts, I head out a little before 7 a.m. on a quiet Friday. I head from city to suburbs, finally making my way down a quiet, peaceful street Norman Rockwell would have painted.

The sun is shining, the birds are chirping and the world seems still. But my heart is racing. As I drive farther and farther down Bartman's parents' block, looking for his address, I begin wondering whether anybody is suspicious of my car. My heart beats faster and faster, thinking some suspicious neighbor is going to phone 911 and a patrol car is going to pull up screeching and blow my cover.

Finally, as the street comes to an end, I see the Bartman home. Tucked back into a wooded lot with mature trees and curious squirrels, the white bi-level home looks warm and inviting.

Four vehicles sit in a circular driveway, two of which -- a shiny black Acura and a generic black pickup truck -- look like they could belong to a man in his late 20s. Inside, the house appears quiet. The drapes are drawn. The doors and windows are closed. I park across the street and wait. A neighbor eventually walks outside, picks up his morning paper and stares at me, likely wondering why this rental car with Kentucky plates has been sitting in front of his house for more than an hour. That's the moment when I flash back to something Cohen told me earlier in the week.

"I'm not going to say people don't drive by, but I don't pay attention," he said. "It's a quiet street -- everybody looks out for everybody else."

I feel like a stalker. More dirt-digging private investigator than entrepreneurial journalist. More People Magazine than ESPN. Hoping to quell the neighbor's suspicions and avoid a loitering ticket, I drive off and find another spot at the end of the street to wait.

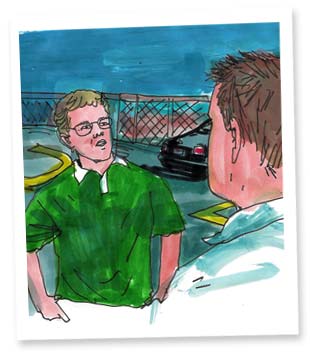

Boredom settles in. I wait for something, anything to happen, listening to WGN Radio's hype of the Cubs-Red Sox series to keep me awake. Then, at a quarter of nine, the Acura pulls out of the Bartman driveway. I don't know who's driving, so I switch the radio off, throw the newspaper on the floor, shift the car into drive, and slam on the gas, doing everything I can to catch up to the car.

At the first intersection, the car is nowhere to be found. I can turn left. I can turn right. I choose right. My heart is pounding. My mind is racing. Could it be him? What am I going to say? What am I going to do? What if he knows I'm following him? And the worst thought of all: What if I lose him?

Lucky for me, I guessed right. The Acura is progressing at the pace of a snail, puttering along in the right lane. I proceed ahead, secretly disappointed I'm not in a high-speed chase on a cable-news channel. At the next stoplight, I slowly pull forward in the left lane. The car stops. I look to my right.

It's Bartman.

"I'll go over this with my legal team, and we'll get back to you. Does that sound good?."

-- Steve Bartman

His glasses look more modern, his hair thinner, but his facial features are the same. Same nose. Same lips. Same chin. It's definitely him.

My heart eclipses first-time-on-an-upside-down-roller-coaster speed. The guilt of stalking him outside his house has been replaced by adrenaline. But now what? Do I drive to his office and corner him in the parking lot? Do I let him go, like a fresh catch you feel sorry for and throw back?

With so much swimming inside my head, I fall back on the road, so Bartman doesn't realize I'm tailing him. You pick up a lot watching late-night detective shows. But then, disaster hits. He turns right. The cars stacked up behind him prevent me from getting over and turning. A forest preserve on both sides of the highway forces me to drive almost two miles before I can turn around.

I lose him.

Deflated, I pull out a map and make my way to Bartman's workplace. Once there, I start weaving my way through the endless maze of parking decks, lots and garages, hoping to find his car. After 40 minutes, I spot it.

Now that I've seen Bartman in the flesh, I'm determined to speak with him. I decide to come back at the end of the workday, hopefully meeting Bartman when he heads home for the weekend.

"Steve, you got a second?"

Seven hours later, I'm back in the same parking lot. I drive back up the ramps, back to the southwest corner where I last saw Bartman's car. It's still there.

At 4:45 p.m. on a Friday, I figure it's only a matter of minutes before the third-floor parking garage door will swing open and Bartman will walk out. My stomach is doing backflips. My palms, my forehead, my forearms, they're all sweating.

The answers to that horrible night, the answers to whatever became of Bartman, are so close. I'm anxious. Nervous. Bored. Uneasy. It's like sitting in the waiting room of a dentist's office, wondering when the receptionist will call your name. Every 10 minutes, the waiting room door swings open, the receptionist looks you straight in the eye and you clench your teeth, only to hear the name of someone else.

By 7 p.m., it's a roller-coaster ride that I've hopped on and off about 50 times. There's no sign of Bartman. No sign of my answers. His car and mine are the only two left on the roof of the garage. I worry that he saw me hovering and left with a friend. I wonder if he went out for beers with a coworker. Maybe his car died and he caught a ride home. Or is he really staying this late on the final day of the work week?

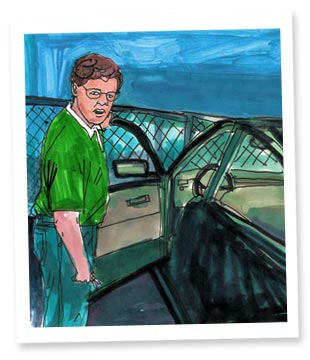

I decide to wait one more hour. I've come this far, why quit now? Fifteen minutes later, the door again swings open.

This time, it's Bartman.

I jump out of my car, walk over with my hand extended and introduce myself.

"Steve? You got a second?"

"Yeah, sure," he says, in a voice so friendly, so accommodating, he could pass for Mr. Rogers himself. "How can I help you?"

I tell him.

"I'm sorry to do this here, like this. I feel pretty uncomfortable, but I want to introduce myself. My name is Wayne Drehs. I'm a die-hard, lifelong Cub fan and a feature writer for ESPN.com.

"My editors have assigned me a story about you, and I've wrestled all week with how to write it. I came to the conclusion that the best thing to do is to just talk to you, ask you, have you tell your story.

"I'm here to ask you for an interview."

He doesn't scream. He doesn't yell. He doesn't take a swing at me. He's completely unflappable. He looks at my business card, looks back at me and smiles. His reaction doesn't seem real. Like it's happened so many times he knows what to do. Or like he has been trained for this. Or maybe, just maybe, he really is the phenomenal guy his friends, family and neighbors are protecting.

For whatever answer he has, I have a grocery list of rebuttals ready.

I can't right now. How about later?

Leave it in the past. But you're a part of history.

I have nothing to say. The story deserves your voice.

But then he comes back with this: "I'll go over this with my legal team, and we'll get back to you." He even opens the door for my response. "Does that sound good?"

I'm shocked by his poise. His composure. His eye contact. The fact he has a legal team. And the words "Steve Bartman" staring back at me from his hip-bound name tag. I stutter in response to his bulletproof answer.

"Uhh, yeah, sure," I mutter.

It isn't over. Bartman then goes on the offensive, continuing to look at me as he explains -- still in his soft, friendly, levelheaded tone -- that he isn't exactly pleased with me jumping out of a car to interview him.

"Just for the record," he begins, "I wouldn't recommend that you do this again, especially on [company] property, because it's just not a good impression if you want me to do something with you."

I tell Bartman that I understand, but that I just wasn't sure of the best way to get in touch with him. I explain that we're the same age, that we're both lifelong Cubs fans, that my family went to Arizona for spring training every year just like his. And that the only way I truly felt I could convey that was to see him in person. To look him in the eyes, to have him look me in the eyes and see what I was trying to do.

Bartman tells me not to worry about it and then peels back a thin layer of his armor-protected personal wall.

"Hell of a game today, huh?" he says, referring to the Cubs' 14-6 drubbing of Boston. "They were hitting the ball all over the place."

"Sure was," I tell him, pointing to my face. "That's where this lobster-colored sunburn came from. They looked great."

For those 10 seconds, we share a moment. Cubs fan to Cubs fan. One troubled soul to another. Bartman nods, smiles and begins to get in his car. But I refuse to let him.

With clouds rolling in and thunder starting to crackle in the distance, I stand at a crossroads. To the left, the desire to tell Bartman I'm sorry. That all Cubs fans are sorry. For the T-shirts, the death threats, the phone calls -- all of it. Any one of us could just as easily have been in that seat. But to the right, the desire to ask just one question, to get just one answer. I'm a reporter. Steve Bartman is standing before me. I have to ask him something. I have to ask how he's doing.

But my brain -- and my heart -- veer to the left.

"Steve," I tell him, "I've got one thing before I leave. Regardless of what I do for a living, regardless of the way this all might seem to you, I want to apologize. I want to genuinely apologize, on behalf of all Cub fans, for all the crap you've had to deal with.

"I think it could have been any one of us. And I truly wish you the best. I truly hope you're able to move on and live a happy and prosperous life."

Bartman climbs out from behind his car door and extends his hand. We shake.

"Thanks," he says. "I really appreciate those kind words."

From there, he gets in his car and closes the door. I walk away, shaking at the thought of what had just happened. Some might say I blew it, refusing to ask even one question. But there were still plenty of answers. Steve Bartman appears to be doing just fine. He still loves the Cubs, he still follows them as religiously as he ever did and, at least on the surface, his life appears peaceful.

Sure, there's the occasional reporter who jumps out of a parked car or the SportsCenter anchor who references the infamous fan, but he's moved on.

It's his only choice.

Wayne Drehs is a staff writer for ESPN.com. He can be reached at wayne.drehs@espn3.com.