Olympics: Wieber Fever

he anticipation is always the worst part.

he anticipation is always the worst part.

Her foot taps. Her thumbs jab furiously at the screen of a purple iPhone. She shifts in her chair, switching from cross-legged to one leg up to a more relaxed, legs-outstretched position. But who is Jordyn Wieber kidding? She's trying to focus on the questions, on giving thoughtful answers, but inside, she's a tangle of nerves and excitement.

How can anyone be expected to remain calm at a moment like this, when 12 years of early-morning workouts, bruises, bumps and missed birthday parties are all about to pay off? When it happens, will she freeze? Will she scream? Will her knees turn to Jell-O? God, what if she cries, and on national television? How embarrassing! Thinking back, the stress of World Championships was cake in comparison. But this? In a few hours -- four and a half, to be exact -- Jordyn Wieber, 2011 world all-around gymnastics champion and 2012 Olympic hopeful, just might, maybe, possibly … meet Justin Bieber.

After winning a team gold and the individual all-around title at worlds in October, Wieber made it known she wanted to parlay her gold medals into an opportunity to meet The Beebs, the performer to whom she believes she is inextricably tied. They're both small-town kids with really big dreams who beat the odds to become world renowned at what they do.

espnW: In Her Own Words

With the Olympics six months away, Jordyn Wieber blogs about her plans leading up to trials in June. In one word: training! espnW: Athlete's Life

With the Olympics six months away, Jordyn Wieber blogs about her plans leading up to trials in June. In one word: training! espnW: Athlete's Life

• For more on Wieber and USA Gymnastics, visit usagym.org.

Wieber told anyone who would listen that she -- and her teammates, of course -- would like to meet Bieber. Then she sent out a tweet to her nearly 9,000 followers:

"Now that we are world champions…can we meet Justin Bieber yet? #welldeserved … Who has connections!?!?"

Word spread fast. In November, a producer from "Ellen" called the Wiebers and expressed interest in having Jordyn on the show. Yes, they had seen the tweets. When Jordyn's mother, Rita, asked the producer about Bieber, she was told he was "really busy." Either way, the Wiebers were playing it cool. Bieber or no Bieber, Jordyn was booked for her first major TV appearance.

Ten weeks after sending out that tweet and one day after the start of the second semester of her junior year, 16-year-old Jordyn and her mom are sitting poolside at the Sheraton in Universal City, Calif., enjoying a 60-degree temperature hike. It was in the teens when they left DeWitt, Mich., yesterday.

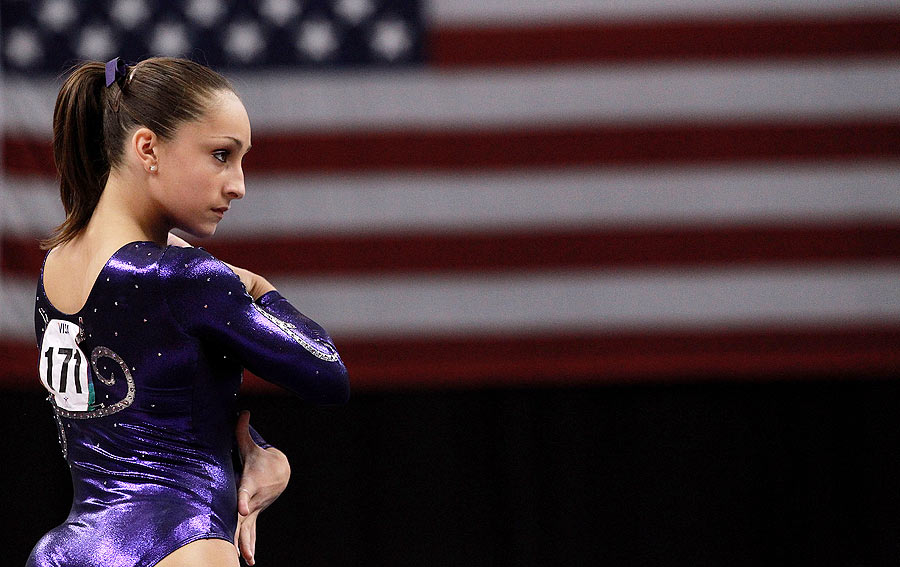

"This is like my first big thing," said Jordyn, who's wearing striped shorts, a white lacy top with cheetah print along the neckline and her dark hair pulled back tightly into the same perfect ponytail she wears during competition. At 5-foot-2½, she looks almost tall for a gymnast. But any doubts about her sport of choice are erased the moment she reaches to shake your hand. Her biceps are visible through the loose sleeves of her shirt and her forearms would challenge the grips of any long-ball hitter in the majors.

"Sometimes the guys at school are like, 'Whoa, you have huge guns,'" she said. "I take it as a compliment."

Wieber speaks much like she performs on floor. She takes long, breathy pauses and sets up answers that flow quickly and powerfully, audible exclamations punctuating each thought. Then, just as quickly as she starts, she stops and awaits the next question. No extra movements, no unnecessary words.

"My friends think it's pretty cool I'm going to be on the show," she said. "But really, they all just hope Justin will be there." She takes a beat before adding: "I do, too."

This is not Jordyn's first time in Los Angeles, but it feels different. So much has happened in the past year, this trip feels less like an obligation and more like a reward. After suffering through a torn hamstring and an ankle injury for much of 2009 and 2010, Wieber was all but unbeatable in 2011. In her first year on the senior circuit, she won her second American Cup all-around championship in March, an all-around title at the Visa National Championships in August and the all-around title at worlds.

Wieber is, by all possible measure, the gymnastics "It Girl" headed into this Olympic year. By the time the London Games roll around in late July, Bieber Fever might drown in the wake of Wieber Fever, a movement that began last fall in DeWitt, the tiny central Michigan town that can now lay claim to being the birthplace of the best gymnast in the world.

Born With Balance

When Wieber was about 11 months old, her dad, Dave, noticed something different about his third child: muscles. In her legs, in her arms, even in her abs. Seriously, a 1-year-old with abs. "They were tiny," Dave recalled. "But they were noticeable."

One morning, when Dave sat Jordyn on a changing table, she did something he was certain neither of his first two children would have been able to do at the same age: She pulled herself up to a standing position and then lifted one leg -- without leaning to put her arms on his shoulders for balance -- and stood like a flamingo as he slipped on one pant leg, and then the other. "We'd already had two kids, so I knew that was unusual," Dave said. "She couldn't even walk, but she had this uncanny sense of balance."

It wasn't just the muscles and the balance. Rita took 3-year-old Jordyn for a regular checkup at her pediatrician. In the waiting room, Jordyn selected a toy out of a box and played with it until she and her mom were called in. The toy, the nurse told young Jordyn, had to stay in the waiting room. As she sat the toy down, Jordyn began to cry. In the exam room, her crying continued. And continued. Forty minutes into the visit, she was still inconsolable.

"We tried everything to distract her -- a balloon, treats -- but nothing would take her mind off of that toy," Rita said. "The doctor said to me, 'This isn't normal. At 3, you can distract a kid in a few minutes. Maybe she's different in some way, gifted.'"

At the end of the visit, the doctor suggested Rita stop by the library and pick up a few books, do some reading. To this day, she's not exactly sure what the doctor was suggesting; did Jordyn have Asperger's syndrome? Maybe. An off-the-charts IQ? Perhaps. But Jordyn had neither of those things.

"I think her gift is her focus," Rita said. "From that very young age, she could get into a zone and nothing would distract her. She could have used that focus to do something else, but I think she found her passion really early in life. You always wonder what your kid would be great at if you'd just exposed them to it. I don't think we have to worry about that with Jordyn."

When people ask Jordyn's parents or coaches what it is that made her so great, they tell them there is no secret formula for her success. She has intense focus, she loves gymnastics, and she works harder at it than anyone else in the world.

They understand that now, but when the Wiebers first signed their daughter up for gymnastics lessons, neither of them knew anything about the sport. Dave knew football and basketball, the sports he excelled at throughout high school. Rita was a sprinter and long jumper at Central Michigan, where she and Dave met and fell in love. Her one brush with gymnastics, in ninth grade, ended with a broken toe courtesy of a failed run at the vault. But when Jordyn was 4, Rita took her to a moms-and-tots class at Twistars Gymnastics a few miles from their home. That's where you take kids with great balance and a surplus of energy, she thought. "Even then, you could see this get-it-done attitude, this competitiveness," Dave said. And she really seemed to like rolling and flipping around in the gym. "She just seemed really happy."

At age 5, Jordyn came home from classes and cartwheeled around the house; a year later, she showed off for her friends by pressing into handstands. She was a natural athlete, but she was born to perform.

"At that time, my only knowledge of gymnastics came from my one year in high school, watching the Summer Olympics and this scary book I read [called], 'Little Girls in Pretty Boxes,'" Rita said. "She loved it, but in the back of my mind, I was thinking, 'This is dangerous. People have broken their necks, died.' But I had faith in her coaches and their training. And besides, I thought, those stories are just about elite gymnasts. Jordyn will never be elite. She's only 6."

But to the trained eye, even then, Wieber showed promise. At age 8, she began competing locally; by 10, she began traveling to regional competitions, as well as a few held out of state. She was winning events on a regular basis, always a threat on vault and beam and in the all-around competition. Her routines included some of the most difficult tricks attempted by kids her age, and she had power and showmanship well beyond her years.

"I knew she had it when she was 7 or 8," said Kathryn Geddert, who, along with her husband, John, has coached Jordyn since she walked into Twistars. "Other kids would stop and watch when someone else's floor music would come on, but Jordyn was hard to distract. What separates her from everyone else is her focus. She knows what she wants to get done and never loses focus on her goals."

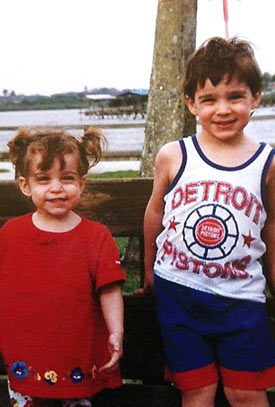

When Jordyn had a competition on the road, the girls and their parents shared rooms to cut costs, so it made sense that Rita would travel with Jordyn while Dave stayed home with Jordyn's three siblings -- Lindsay, now 24 and a medical student at Michigan State; Ryan, 18 and the quarterback of the DeWitt High football team; and Kyra, a 12-year-old soccer player. When it was possible, Rita and Dave both attended Jordyn's competitions while also making sure to be in the stands for their other children's events back home. It was hectic, but a happy kind of hectic.

"We've never been a family-dinners-around-the-dining-room-table kind of family," Jordyn said. "Everyone's always running in and out from school and practices. We're a really active family. We aren't competitive with each other at all. We're really, really close."

But shortly before Jordyn turned elite -- the level from which Olympic gymnasts are chosen -- at age 11, Rita noticed a transformation was taking place within her, as well. She had morphed from a neophyte gymnastics mom into a 24-hour-a-day, gymnastics-obsessed helicopter parent.

"I have four kids, but I was getting so absorbed by Jordyn's gymnastics that I was thinking about it 99 percent of the day," Rita said. "I thought, 'What if she decides she doesn't want to do this anymore? I have to be OK with that. I don't want to be the one crying over it.'"

So, at her husband's nudging, she resigned from the booster club, volunteered only when she was asked to do so and stopped signing up for extra days in the carpool. Five years later, she's thankful she had the self-awareness to take a step back, a move that was good for both her relationship with her family and her own well-being.

"Gymnastics is a strange sport in some ways," Dave said. "When I drove the carpool, I dropped Jordyn off and picked her up when practice was over. Some parents sit for hours watching practice, and it's not healthy. I would never stay and watch my son play football. Once I drop him off, it's up to the coaches to coach him."

Rita said she's not the only mom who has gone through what she did, and she wants to help other parents new to gymnastics avoid the same mistakes.

"People are always asking me what it was like to raise Jordyn," said Rita, who is writing a book on the subject and hopes to have it published by the end of the summer. "But only a small part of the book will be about elite gymnastics. Most of it is informational, for parents who started out like me. What is competitive gymnastics? How do the levels work? What is it like to deal with the coaches? How do you know when you've gone overboard?"

Maintaining A Low Profile

Once mom and daughter were both on track, Jordyn turned elite. That's when the real commitment began. Twice-a-day practices, longer hours in the gym and, after two years, a decision: to attend high school or opt for home schooling, a popular choice with many gymnasts on the Olympic path. Rita, who now works as an ER nurse, has a Master's degree in exercise physiology and is a former special education teacher, so education is important to her and Dave, the director of Michigan operations at Optum, a subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group.

"You can always go to college, but you can't re-do high school," Rita says. "We felt strongly about her getting that experience."

Fortunately, Jordyn agreed. Although gymnastics has traditionally been a sport populated by athletes who move out of their homes at a young age to train with well-known coaches, Jordyn wasn't interested in that lifestyle. And she knew it wasn't the only way. Shannon Miller, the most decorated American gymnast in history, was a kid from a small town just like her who became a world champion while attending high school. So did Shawn Johnson and Bridget Sloan, the past two American all-around world champs.

"I like having a separate group of friends to go to the movies with and get my mind off gymnastics. I like being a normal student," Jordyn said. "I think it's cool to get to be an elite gymnast and go to school. It's good for the next generation to see. It keeps you balanced."

At school, Wieber tries very hard to maintain a low profile. She doesn't like attention and doesn't flaunt her success. She attends two classes per day (English III and Nutrition & Foods) between morning and evening practices and completes the remainder of her courses online.

"I'm used to my schedule by now," she said. "I've been doing it since sixth grade." Although her first practice doesn't begin until 8 a.m., Wieber wakes up at 6:30 to eat breakfast and lounge around. "I'm a morning person."

When she can, Jordyn attends basketball games and school dances. This past fall, she spent her free Friday nights cheering on Ryan as he quarterbacked the DeWitt Panthers to a 9-1 regular season, even though she "doesn't know the first thing about his sport."

Which is OK, because gymnastics terms all sound Russian to Ryan.

"I have so much respect for the way they practice and how much they work at their sport," said Ryan, who plans to attend Central Michigan next year. "But I don't understand how she can control her body that way. I watch her competitions on TV and I've been to one as far away as Chicago. And she comes to football games when she's not swamped with practice. It might seem weird to some people, but there's no sibling rivalry between us. We support each other."

This past fall, it was tough to judge who was the more popular Wieber at DeWitt High. Jordyn was receiving worldwide attention, but Ryan was the local star and a regular on the preps page of the local papers. He took the Panthers to the district final, where they lost to East Lansing 23-14. In his best game of the season, he accounted for five of DeWitt's six touchdowns, running for 132 yards and four scores and passing for another, in a 42-6 win over Owosso. In the stands, the DeWitt section was populated with students, Jordyn amongst them, wearing surgical masks and T-shirts with the words "Wieber Fever" and Ryan's face atop a cartoon football player's body. The following week, Ryan led his team to a 34-17 homecoming win over Fowlerville just days before Jordyn took the floor for the final event of the all-around competition at worlds. Although Jordyn was already on her way to Tokyo and missed the game, Rita and Dave were in the stands. It was "parents' night."

The next morning, they hopped a plane to Tokyo, watched Jordyn win the individual all-around competition and then headed straight to the airport so they could return to DeWitt for Ryan's next game, a 22-20 overtime loss against Portland High.

"We didn't want to miss any of our son's games this season, but we also knew Jordyn might never go to another world competition after London," Dave said. "As busy as it was, it was a once-in-a-lifetime thing. We will never have something like the three-month period we went through last fall. It was fantastic and fun and something I will always cherish."

Double Trouble

Of course, now that she is world champion, Jordyn Wieber is cursed. Since 1972, only one reigning world all-around champion -- Lilia Podkopayeva of Ukraine in 1996 -- has followed up her win with an Olympic all-around title. Many have come close. As recently as 2008, Johnson -- the 2007 world all-around champion -- took silver to teammate Nastia Liukin in the Olympic all-around competition. But Johnson entered the Beijing Games as Wieber will -- the hands-down favorite to win gold. Johnson was called, as Wieber will be, everything from "America's Sweetheart" to "It Girl" to "The Next Mary Lou." But despite leaving Beijing with silver medals in the individual all-around and floor competitions, a gold on beam and a silver in the team competition, the public perception was that Johnson had failed.

"I remember being in the media line right after the individual all-around and a woman asked me, 'How does it feel to lose?'" said Johnson, the only gymnast to follow up an Olympic season with a win on "Dancing with the Stars." "I was like, 'Lose?' I hadn't thought about it like that. I'd just won a silver medal in the Olympics. I'd done my best. I was so proud. Wasn't I supposed to be?"

Managing outward expectations while retaining the laser focus she's known for will be Wieber's toughest challenge in the coming months. The worlds/Olympic double is difficult for many reasons: It's tough to push hard in training while staying healthy for such a long stretch, judging styles change from event to event and the rest of the field begins gunning for the girl at the top. But the most difficult challenge is motivation and focus, and the possibility of Wieber losing either of those traits will keep U.S. national team coordinator Marta Karolyi up at night and could keep Wieber off the top of the podium.

"The most important thing Jordyn can do is not train as if she's the world champion," said Miller, the 1992 Olympic silver medalist in the all-around, the 1993 and 1994 world all-around champ and 1996 Olympic balance beam and team champ. "She must train as if she wants to be the Olympic champion. I've always believed it's important to have an underdog mentality."

But if anyone can beat the curse and become the first American woman to achieve the double, Wieber's coaches believe she can. They believe that same little girl who could block out the music and chaos in the gym will be able to block out the noise as she prepares for the toughest five months of her young career.

"Worlds opened Jordyn's eyes to the fact that she really is that good," Kathryn Geddert said. "It was a close competition with the Russians, and it gave her confidence knowing how well she did against the best in the world. We'll make some upgrades to her routines that will increase the start values and work on the details."

That's saying a lot, considering Wieber already competes some of the most difficult routines and tricks on every apparatus, including a standing full on beam, a Tkatchev release and double-twisting double-tuck dismount on bars and an Amanar vault (a 2½-twisting Yurchenko), which has a start value of 6.5. For context, that's nearly seven-tenths higher than the start value of the double-twisting Yurchenko performed by Viktoria Komova of Russia, who took silver at the World Championships and is poised to be Wieber's biggest threat in London. Those difficult routines are why Wieber was able to hold on to her lead at worlds despite a form break on bars and a step out of bounds on floor.

Wieber said those mistakes have both motivated her and given her a confidence she didn't have before last year.

"The fact that I had a mistake on bars in both comps [nationals and worlds] makes me want to work harder to make my routines more consistent, but also tells me I am able to stay strong during a competition, take my mind off a mistake and come back even stronger on the next rotation," she said. "I'm taking this year one step at a time and not focusing too much on anything down the road."

After Wieber won the world title, she was faced with another decision: to turn pro or continue competing as an amateur. Turn pro, and a gymnast becomes eligible for sponsorships and endorsement deals; but in exchange for a paycheck, she forfeits her college eligibility (Wieber is eyeing UCLA at the moment) and the chance to continue competing into her college years. She can also continue to compete at the elite level and, as Johnson and Liukin are currently doing, make a comeback run at the 2016 Games when she's 20 and a college sophomore. She can also stay involved in college gymnastics as a coach or work at a nearby gym.

After two weeks of talking with her parents and coaches, Wieber decided turning pro was the best decision for her. Once she did, the Wiebers were inundated with media requests and sponsorship offers.

"I didn't think it would be nearly as big a deal as it was," Rita said. "A lot of people in the gymnastics media were actually negative when Jordyn announced her decision to turn pro. They said she would never be able to make enough money to pay for college, especially at a school like UCLA, but she already has."

So far, Wieber has signed endorsement deals with three companies. At Kellogg's, she will be the only gymnast featured in their Team Kellogg's campaign. She will appear in commercials for Auto-Owners Insurance and in print advertisements for Procter & Gamble. The first two companies are based in Michigan, which made the decision to sign with them an easy one for Rita, who is acting as Jordyn's agent until the Olympics are over.

"We wanted to limit how much she did before the Olympics, so we said we would sign three deals, and we've done that," Rita said. "If we'd signed with an agent, her time could become their time and we don't want that right now. This is her time to focus on gymnastics."

But before Jordyn is willing to talk Olympics, she must first make the team. This year, for the first time since 2000, the entire five-woman Olympic team will be selected at the Olympic trials, which will take place June 28-July 1 in San Jose, Calif. At the past two trials, the top two finishers at trials earned automatic spots on the team, but the remainder of the squad was chosen at a selection camp held at the Karolyi Ranch in the weeks following the event.

"I'm a little nervous, but that was the decision and I hope we will be able to handle it," Karolyi said. "I always like to select the team two days before we leave the country and this will be different. We will have to figure out how to deal with this extra time."

The feeling from gymnasts and coaches, past and present, is this is a good thing for the sport. It makes the trials more exciting for the fans and rewards the gymnasts who do well there. Many in the sport disapproved of the Karolyi way, saying the pre-Olympic camp caused overtraining and placed unnecessary stress on the athletes.

It's hard to argue with that assessment. The 2004 and 2008 teams were heavy favorites in the team all-around heading into the Games but underperformed and returned home as silver medalists. This year's team will again be the heavy favorite for team gold. And Jordyn wants to make good on a promise she made to her coaches in 2008.

Jordyn watched with her coaches as the 2008 U.S. national team took silver at the Beijing Games. "She looked at me and said, 'That's OK. We'll get 'em in 2012,'" Kathryn Geddert recalled. "I thought, 'Isn't that so cute?' But she wasn't joking. She meant it. Now that it's here, I'm not sure any of us are ready."

Except for Jordyn, the steeliest of the bunch.

A Girl Can Dream

The call comes at 6:30 p.m. After 10 minutes of rehearsal on the bars, a few minutes in hair and makeup and an hour spent in the greenroom, it's Jordyn's turn to walk onto the stage and take a seat in the chair opposite Ellen DeGeneres.

"You won the World Championships. Is that a relief or is that more pressure?" DeGeneres asks, a couple of minutes into the interview.

"It gives me confidence going into the next year. Winning World Championships was a huge goal," Jordyn says. "I loved the feeling of going out there and showing off."

"You have another goal," DeGeneres says, as a screen on the back wall flashes Jordyn's post-Tokyo tweet. "You tweeted about something."

Jordyn smiles nervously. "Yes, meeting Justin Bieber."

Well, DeGeneres tells her, "It seems like you deserve that. If you're a world champion, you should meet Justin Bieber. I'm going to see if I can arrange that."

It is clear as she finishes this last sentence that Bieber is not in the building. Although he did appear on the show Wednesday, he taped his segment earlier in the week.

"OK, thank you," Jordyn says, her disappointed expression gone by the time she's finished her thought.

If history has taught Jordyn anything, it's that disappointment is fleeting. There is always another competition, another goal, another invitation to "Ellen." She'll get her chance to meet Bieber. She's sure of that now.

But the anticipation. The anticipation is always the worst part.

Alyssa Roenigk is a senior writer at ESPN The Magazine and ESPN.com.

Follow on Twitter: Alyssa Roenigk, espnW, @ESPNmag and ESPN_Reader.

Join the conversation about "Wieber Fever."