Jackson's greatness is unquestioned

The debate over Phil Jackson's legacy is comical on many levels, including the most basic: the idea that there even needs to be a debate. Seriously, you concoct an argument that diminishes his achievements because he won championships with great players? That's genius. And Randy Johnson's 301 wins should be tainted because he has a great arm.

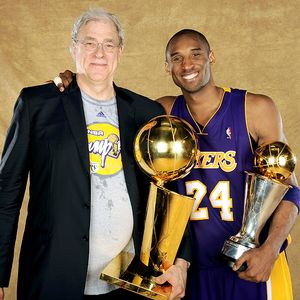

It's the never-ending quest to create context. Great achievements can't exist on their own merit. They must be dissected by era, by competition, by personnel, by temperament, by style. Jackson has 10 titles, more than any other NBA coach, so let the parsing begin. Red Auerbach won his nine in one stretch with one team, which some people consider a mark against Jackson. And Jackson won with three of the 10 most dominant players in history (Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Shaquille O'Neal). That's another mark against Jackson, somehow.

Everything has to be an argument, the louder the better. You have to pick sides. Jackson would never touch a rebuilding situation. Auerbach's teams were playing against inferior competition in a time of infrequent player movement. Jackson drafted behind his best players. Auerbach had Bill Russell.

Would another coach with a full but title-free career -- for the sake of argument, let's call him Don Nelson -- have been able to match Jackson's achievements if he had been placed in the exact same situations? We'll never know, which doesn't stop us from speculating. To me, Jackson's greatest talent is his ability to get out of the way. It's a talent that isn't shared by many in his occupation.

The greatest temptation is to overcoach, and the guys who overcoach receive the most credit. It always comes down to the play they draw up or the pivotal timeout call. (Granted, this is far more a scourge in the college game, but it exists in the NBA, too.) Guys who are trying to save their jobs or prove themselves are usually the ones who call a different set every possession and slow the game to a crawl. There are exceptions, of course -- some teams function best in half-court sets -- but it's unusual to find a guy who can tailor his coaching to the talent on the floor. It's one of the reasons I think Rick Adelman is the most unappreciated coach in the NBA. He has a knack for knowing how much leash to give -- a lot with the Chris Webber-Jason Williams-Vlade Divac Kings, not as much with the Yao Ming-Ron Artest-Luis Scola Rockets.

If there's genius in getting out of the way, Jackson has perfected it. I'd make the case that it's a tougher approach to follow because it shifts a huge share of the credit to the players. Obviously, he has had great players, but he's managed to create a system in which the players can excel, then has trusted them to execute it. Does that make him a button pusher or a master of preparation? And, yes, it does help to have a guy like Kobe who can create when the offense breaks down. It also helped Auerbach to have Russell coming from the weak side to deflect shots into the hands of Sam Jones or John Havlicek when the Celtics' defense broke down.

Part of the tendency to diminish Jackson is understandable, because it's difficult to overemphasize the utter lack of competition the Magic provided. Everything about them screamed, "We beat the Cavs. We made it to the Finals. We're good with that." If you want to delve into the comparison game, imagine Jackson's Jordan-Scottie Pippen-Dennis Rodman Bulls team playing this year's Magic. The Bulls could have won every game by 40. The biggest upset of the Finals came after Game 5, when some people in Los Angeles thought the Lakers' win warranted public mayhem. Most people I know just went to sleep afterward. Even Lakers fans.

But as former Jackson assistant Jim Cleamons told The New York Times, "Every situation that Phil has coached in, the team hadn't won before he got there. That, too, is a fact."

During the Bulls' training camp before the record-breaking 1995-96 season, I spent quite a bit of time with Rodman while I was writing his autobiography. The first day I arrived, I was supposed to meet Rodman in the lobby of the Berto Center in Deerfield, Ill. Like most things involving Rodman and a schedule, this didn't happen as planned. Eventually, I wandered around conspicuously enough that someone brought me to the entrance to the weight room, where Rodman and Jordan were the only ones working out.

Rodman waved me in. I knew I had no business being in there, guest of Rodman or not, but I also knew it was the kind of situation that was too good to pass up. Rodman introduced me to Jordan, who shook my hand and didn't tell me to leave. I was kind of amused by the whole deal, and after spotting Rodman on the bench -- it turned out I was invited in partly so I could work -- I was getting ready to leave when Jackson came through a door.

Rodman introduced us, and Jackson said, "You really shouldn't be in here." I agreed and shrugged with a look on my face that said, "Hey, could you blame me?" Then he laughed and closed his eyes tight with a look that said, "Can you believe I have to deal with this all year?"

But he did, and he did it in a way that humanized the people who played for him while bringing out the best in them as athletes. He dealt with Jordan-Rodman-Pippen, and then he dealt with Kobe-Shaq, and then Kobe-Kobe-Kobe. Great players, outsized personalities, all of them different. And he won 10 times. Easy shouldn't be the first word that comes to mind.

ESPN The Magazine senior writer Tim Keown co-wrote Josh Hamilton's autobiography, "Beyond Belief: Finding the Strength to Come Back," which is available on Amazon.com. Sound off to Tim here.

Subscriptions

Subscriptions