After "the Tim Donaghy affair," I have been hardcore in favor of greater transparency in the referee game.

I hear from a lot of basketball fans who think NBA referees are blind, idiotic, corrupt, demonic or worse. The only real evidence on the other side of the ledger is some vague promises from the league that NBA referees are the best in the world. (Listen, it may well be true. But show me, don't tell me.)

The debate quickly loses meaning from there, as essentially no one has any real arguments of substance.

I'm hungry for more real evidence -- better public documentation of which calls are right and which are wrong, as well as a better sense of who our referees are, and what the job of a referee is like.

As one small step in that process, I asked the NBA to let me interview one of the best-known and most controversial NBA referees: Bennett Salvatore.

As one small step in that process, I asked the NBA to let me interview one of the best-known and most controversial NBA referees: Bennett Salvatore.

Referees, by and large, are not permitted to talk to the media, but the league makes exceptions from time to time for feature stories and the like. They were nice enough to go along in this case.

A 26-year veteran of NBA refereeing, Salvatore has a solid reputation among the various experts I have talked to. But among fans, it's hard to imagine there is a more reviled official.

Salvatore famously made a key call against Dirk Nowitzki in Game 5 of the 2006 NBA Finals after which Dallas owner Mark Cuban held one of the angriest press conferences in history. ESPN's Bill Simmons has named Salvatore the second worst referee in the NBA, and a review of every call of Game 5 by 82games.com found that of the ten debatable calls Salvatore made in that game, an astonishing eight (I'm no math whiz, but that's 80%) favored the Heat -- who ultimately won that game and the championship.

This past Friday, November 9, I ventured to the NBA's offices in Manhattan and spent more than an hour interviewing Bennett Salvatore one-on-one. (Well, it was kind of one-on-one. There were two NBA staffers present on hand, one of whom was also recording the interview.) I had agreed in advance that Salvatore would not answer questions about working with the yet-to-be-sentenced Tim Donaghy, although gambling in general and the effect of the Tim Donaghy scandal were fair game.

The results of our conversation will appear in a series of TrueHoop posts over the next several days. Here is some of what's coming up:

Tim Donaghy fallout, gambling, broken trust, and the perception that referees are not on the up and up.

Bennett Salvatore describes, moment by moment, what happened on that much disputed, game-changing play against the Lakers in 2006, when Steve Nash and the Phoenix Suns got a jump ball when they thought they should get a timeout or an out-of-bounds call.

Remember the closing moments of 2000's Game 7, Knicks vs. Heat, when Latrell Sprewell was granted a timeout while falling out of bounds? And later Sprewell said he had not called timeout? Bennett Salvatore was the referee who granted that timeout, and now he explains why.

A lot of NBA fans first learned Bennett Salvatore's name when he called that foul on Dirk Nowitzki at the end of Game 5 of the 2006 NBA Finals. It was a huge factor in deciding the series, it embittered the city of Dallas, and yet the TV cameras didn't catch much of a foul. Some video you probably have not seen before, and an explanation from Salvatore, may change your view of that call.

Outtakes: Bennett Salvatore buying Santa hats for his entire crew, a pretty great anecdote about Charles Barkley, doing skits with mascots, and more.

The Meeting

There is no getting around the fact that Bennett Salvatore fits a stereotype. When fans peruse the names of referees, fantasizing about which guy might have mob connections, it doesn't take a PhD to linger at his most-Italian of last names. Add to that a history of playing a controversial role in big games and various oddities like having worked for the Italian Federation in Rome, and you probably have a flavor of some of the meanest things people bark at Salvatore from the stands.

The way he dresses doesn't do much to dispel the notion. He's impeccably groomed and decked out in the kind of Italian-style suit -- the cut and fabric are distinct -- that would fit right in on the "Goodfellas" set.

Of course, what I'm describing is 0% evidence and 100% prejudice. Only in the mind of a bitter person is time spent teaching Italians to play baseball anything to do with the mob.

The man I met in that conference room was smiling wide, and extremely welcoming. I had been in the room only a moment or two before it was clear to me that the NBA had made a good PR move by exposing the off-court Bennett Salvatore to the media.

One of the phrases I had heard about him -- brace yourselves, Mavericks fans -- was that he's "such a nice guy." It's not just a line. I put a lot of tough questions to him, and while he ducked a couple of them, he was always thoroughly polite and largely disarming -- the kind of guy who could make you feel comfortable in a restaurant.

Think about it -- it's four people in the room, none of whom really know each other all that well. And we're in the NBA headquarters talking about stuff like: are NBA games fixed? Half the people in the room are presumably there as hall monitors/police.

And you know what? We laughed a lot. It was not adversarial, tense, or weird. I'd happily do it again.

Bobby Valentine's Lifelong Friend and Rival

We started out with the life story. Salvatore has lived his whole life in Stamford, Connecticut, where he was an honorable mention All-America quarterback as well as a top pitcher in high school. In college, Salvatore's C.W. Post football squad was ranked second in the nation, he says.

One of his most intense athletic rivals in Stamford, and a close friend to this day, is former MLB manager Bobby Valentine. Their rivalry persists, as Valentine and Salvatore both have restaurants in Stamford. Bobby V's is what Salvatore calls "more of a shot-and-a-beer place," while Salvatore's steakhouse, Bennett's, is a high-end, critically acclaimed steakhouse. (If your steakhouse clientele includes not just garden variety celebrities like Tim Allen, Rudy Giuliani, and Bernie Mac, but also one of the world's most prominent vegetarians -- Salvatore says the Dalai Lama ordered salmon -- you must be doing something right.)

"My father-in-law," he explains, "owns the property, and before he rented it, he asked me if I wanted to do anything with it. You have to really know what you're doing if you want to run a top restaurant, and I went to school with two guys who were in the restaurant business." Salvatore doesn't take a lot of credit for the restaurant's success: "I'm the hand-shaker," he s

ays. "I never go in the kitchen."

A Referee's Burden

When Salvatore discusses his day job, he is nearly reverential. He talks about his employer like people used to talk about their employers in the 1950s -- back before Enron, when pleasing your boss was a lifelong meal ticket.

At one point I asked him about a controversial call he had made, one for which he has been vilified for years -- and his response included this, which may have been motivated by the league bigwigs in the room, but I believe was from the heart: "It comes along with the territory. It could be a travel in the first moment of the game, as well as a play-ending foul. You have to be strong enough just to do what you're doing, and hope that it's right. But the most important thing is that you know what your employers believe it to be, right or wrong. That's the only way you learn."

I ask him if he has ever made the wrong call. "Sure! Absolutely! I remember one, it must have been 15 years ago. I had a call in Sacramento. It was at the end of the game, and I had scored it a three-point basket, and in fact it was a two. I was wrong. I didn't know I was wrong until afterwards. But it cost the team a game, and I was sick about that. We go in the locker room afterwards, I was sick. I can't repeat on the tape what I said. And I think maybe that's the thing that the general fan doesn't understand the most -- and that's how much we care about our job. And we do. There is no one more upset than the referee if they make a mistake, than that referee. Whenever I talk to anybody, rule number one is -- we make mistakes. We don't want to, but we do."

(Bennett adds that particular bad call nightmare story has a happy ending, in a way: "Today, that would have been overturned by instant replay. That's the beauty of where we've come. To be able to get things right is the greatest thing in the world.")

NBA Referees Always ...

Give superstars and friendly players and coaches the benefit of the doubt, punish rookies and those with hot tempers, issue make-up calls to mistaken bad calls, and cater to the home crowd.

As NBA fans, we hold these truths to be self-evident.

Using much more polite terminology, and sticking very close to the referee PR playbook, Bennett Salvatore swears that's all, essentially, a crock. Point by point:

Superstars, rookies, hotheads, and nice guys: "Whether it's a rookie or a veteran, a nice guy or a not nice guy, our job is not to get into that, and follow the guidelines. It may sound trite, but that's really what we're trying to do. ... Sometimes these ideas come from seeing someone like Michael Jordan. But you have to realize, he handled the ball for his team 60% of the time which means you may go to the line more. We do not give calls to anyone. ... We don't have any relationships with the players and the coaches off the court. But our relationship on the court is professional. They know we're there to do a job, I know they're there to do a job, and we may have a very congenial and respectful working relationship, but there's no break just because you have been in league ten years. Your foul is his foul, his travel is your travel, and we try to maintain that."

Make-up calls: "This is the reason why we don't do that -- I can't tell you how many times I make a call that I think is correct -- and then go into locker room and it's wrong or vice versa. We don't really know. We do what is in our heart and what our mind tells us, but we don't know for sure until we see it in the locker room. So every play is a new play, and your focus has to be on the next play."

Home crowd: "That's what makes us professionals. Our focus on the court does not allow us to be swayed by the noise of home court. ... You have to drown out the crowd. I mean, there's many times my wife might be at a game and she'll say 'boy they really gave it to you after that call,' and I don't even know what call she's talking about. You know, you're so involved, you're so intense on the game."

A Day in the Life of a Referee

For whatever reason I am always curious about the process of people's jobs, and Salvatore was gracious in explaining. Before the game, every day and without fail, he takes a nap. Referees are under contract for 82 games a year, just like the players. Then, as a crew chief, he meets with his crew and organizes a meeting that includes going over the relevant information -- reports from the crew that worked the last meeting between these teams and the like. They take note of which players have squabbled, so they can be alert to any trouble.

They also go online to review video prepared by the league of tough calls from around the NBA. Sometimes that video comes with specifics about how such situations should be called in the future, other times the league solicits thoughts from referees.

And other times, referees hear the hard news about calls they get wrong.

Although there have been rumblings that officials are dissatisfied with the way they are overseen by the league (and even an ongoing shakeup of referee honchos) Salvatore will not admit to any of the league's supposed faults, a big one of which was said to be quotas for this or that call.

"People talk about the quota calls," says Salvatore, "but I don't think there has been grumbling. The idea is not to be used because you didn't have any defensive three-seconds calls or that kind of thing. Let me give you an example. Two years ago the league told me that according to the statistics that my calls that I had incorrect were mostly in the third quarter. I took that to heart. You use that information to look in the mirror. I say OK, let's pick it up a little bit. Maybe you were a little lackadaisical coming out of the half. And now I'm not. And my incorrect calls have gone down in the third quarter. That's the type of use a referee puts that information to. But it's not a matter of ten of these or twelve of that. It's to look for certain areas of your game that you have to be conscious of, certain tendencies."

(Salvatore further adds that he's amenable to some of the changes that may be coming down the pike, for instance publishing video demonstrating good and bad calls: "I don't really know if I have feelings about it one way or another. I think it'll probably wind up to be a good thing, because I think what the public will find is that we're probably right a heck of a lot more times than we're wrong. So I think that the overall truth will be that, and I think that's a good thing.")

After all of the review, getting changed, and limbering up, it's time for the game, during which, he explains, crew chiefs have special responsibility. In addition to having final say on any rules interpretation issues, the chief notes things like wet floors and malfunctioning clocks for a postgame summary and report submitted to the league. The crew chief is also the referee on the spot when instant replay is called for.

After the game and showering off, the crew used to huddle around a laptop to review the game, but now has what Salvatore sees as a major improvement. "It's a giant step!" he declares. "The league has provided us with projectors that plug into the computer, so now we don't have to look at the tiny screen anymore. It makes life a lot easier. It's bigger and easier to see clearly, and you don't have to crowd three guys around the laptop anymore."

Reports and reviews complete, it's time to head to the next city. Here, post-9/11 security has an effect. Referees travel as much as players do, but without private jets. The particulars of flying, in that reality, weigh heavily. (And yes, Salvatore was one of the referees who got in trouble for not paying taxes on income realized by trading in league-purchased first-class seats for cheaper seats.) The referee's contract calls for officials to fly out the same night if the schedule allows. "We used to get on the plane five minutes before takeoff, and that was it," he writes. "Now we're in the airport an hour or two." That means a lot of times, they fly the next day. And it means a lot more time in airports. "It is," says Salvatore, "a fatiguing part of the job."

Another tough part of the job? Salvatore won't complain about it, but nobody likes getting screamed at, questioned, called corrupt, or interrogated by investigators. The unthinkable Tim Donaghy story is in a class by itself. Among the rest of the workforce, a bad call here or there is no cause for alarm, says Salvatore: "We try not to defend ourselves. We're not in defending mode. But rule number one is that we make mistakes. ... We all have kids. We have parents. We just go to work. We work hard. And, above all, if there was any message at all that I had for anybody it's: we give it our best shot, and we will continue to."

More Salvatore Side of the Story to follow in the days to come.

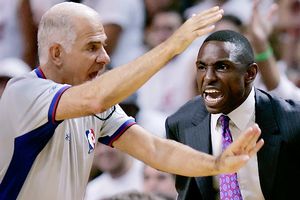

(Photo: Bennett Salvatore at the NBA Finals 2006 with Avery Johnson. Photo by Ronald Martinez/Getty Images.)