Time for some 10 things (plus a bonus item):

1. Chris Paul has some of his snap back

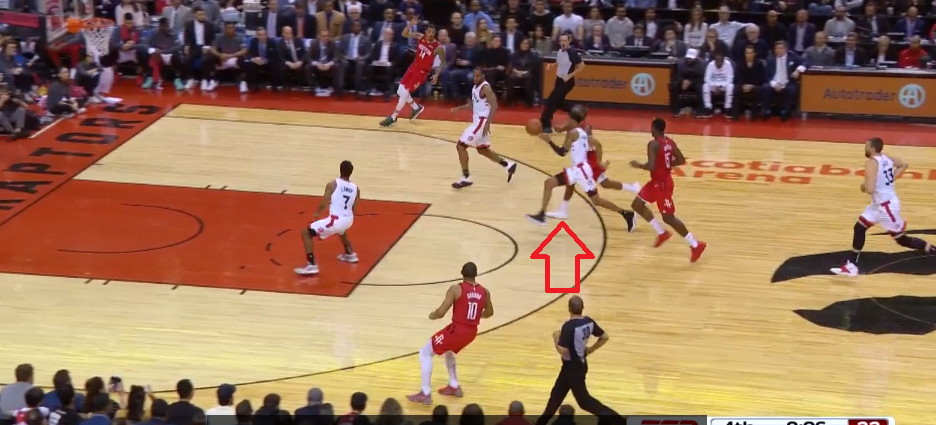

Paul's shooting hasn't come all the way around during the Houston Rockets' climb into the Western Conference's No. 4 spot, but he has his quick-strike swagger back:

What a freaking genius. Look at what Paul sees -- or at least what we can see of Paul's passing angle -- when he slingshots this baby to Eric Gordon:

I mean, come on.

Paul isn't as fast as he once was. He can't blow by defenders -- including big guys on switches -- as easily as he could even last season. He's not a leaper. But when he's healthy, Paul snaps from a standstill into a high-speed lunge with alarming suddenness. He moves in sync with the ball on defense, or even just before the passer releases it. He is almost always anticipatory, not reactive. His brain makes his body faster.

Paul is doing his best work when James Harden rests. The Rockets have outscored opponents by 11 points per 100 possessions in those minutes, and that number has been even beefier -- about 17 points -- since Paul's return from injury in late January. He has a massively positive effect on Houston's wobbly transition defense, a consistent trend through Paul's career, per Cleaning The Glass.

Houston's best lineups haven't quite clicked, even during this streak. The Rockets are about even for the season when Harden and Paul share the floor, and their starting group -- Paul, Harden, Gordon, the indomitable PJ Tucker and Clint Capela -- has been a net negative.

That will change if Paul keeps playing this way.

2. The Joe Ingles-Derrick Favors dance

A stat that might surprise: The Utah Jazz have destroyed opponents by about 14 points per 100 possessions when Ingles and Favors play without all three of Ricky Rubio, Donovan Mitchell and Rudy Gobert, per NBA.com. Ingles has become Utah's de facto backup point guard, and he and Favors have developed a nimble chemistry in the pick-and-roll:

Favors is cagey disguising the direction of his screen. Ingles flips from fast to slow -- or perhaps slow to less slow -- depending on how much time Favors needs to roll deep into the paint, or what tactic would crack open the widest passing lane:

Both can hit floaters or midrange jumpers. Ingles keeps help defenders guessing until the very last second. He has a fake for every part of his body -- eye fakes, pump fakes, and the meanest pass fake since Manu Ginobili was spinning big guys around like tops. It wouldn't surprise me if Ingles has some sort of nose fake we don't know about.

Is this a layup or a pass?

By the time you realize, it's already over.

Favors, meanwhile, is enjoying perhaps his best two-way season. He has canned 64 percent of his 2-pointers. He is healthy and cramming on fools again. Opponents have hit just 48.6 percent of their shots at the rim with Favors nearby, the lowest such figure among 151 players who challenge at least two such shots per game.

Zoom out farther, and opponents have an effective field-goal mark 9.2 percentage points lower than expected -- based on the location of each shot -- when Favors is the nearest defender, the stingiest figure among all rotation players, per Second Spectrum tracking data. Yowza.

The Favors-Gobert combo might not work over heavy minutes, or in crunch time, but Favors is essential to the Jazz anyway (for now). The Ingles/Kyle Korver/Royce O'Neale/Jae Crowder/Favors group has become a fixture of Quin Snyder's rotation.

3. Kelly Olynyk, on his time

After falling to the fringes of the Miami Heat's rotation, Olynyk has re-emerged as a crucial cog and starter as the capped-out Heat try to salvage a third straight blah season. The king of the slow-motion pump-and-drive is averaging 15 points since Feb. 1 on 54 percent shooting -- including 47 percent from deep.

The Heat have outscored opponents by about five points per 100 possessions when Olynyk and Bam Adebayo -- their current starting big-man duo -- share the floor, and even the maligned Olynyk-Hassan Whiteside pairing has surged over the past month. Olynyk is a heady sort, and he's doing his best to chase opposing power forwards on defense so Adebayo and Whiteside can hang near the rim.

With Goran Dragic hurting and Wayne Ellington a tax casualty, the Heat sorely need the threat of Olynyk's jump shot to stress defenses. He's also delightfully patient around the rim, holding his pivot foot and staying low as shot-blockers fly around him -- and using all three seconds of allotted paint time:

He's like Little Mac in there dodging punches until it's safe to strike.

The Heat are only 6-7 since reinserting Olynyk into the starting lineup, but he has helped them stay afloat amid injuries. Olynyk has cracked the 20-point barrier in four of Miami's past six games, including recent wins over Brooklyn and Charlotte with huge playoff implications.

4. Julius Randle, sieve

We hearty souls who have been foraging atop Julius Randle Hill for years always knew he could score, trample entire defenses on the fast break, and dish canny assists when he wasn't getting a little hoggy. It has been nice seeing him flourish as a 20-point scorer with the New Orleans Pelicans.

But there is some trepidation in the Hill community -- more populous now -- given that Randle's ascension on offense has come at the expense of his work on the other end. Some of that is New Orleans shoehorning Randle into defending stretchy power forwards. He just does not have the fast-twitch speed or attention to detail for it:

He is often late dipping into the paint to help, meaning he is also late darting back out:

Randle is still moving toward the paint when Avery Bradley's pass to Danilo Gallinari is airborne in the other direction. That is death.

Randle hasn't fared much better protecting the rim. He is 451st among 494 players in the defense-only version of ESPN's real plus-minus -- a stat that often makes big men appear better than they are (hi, DeAndre Jordan.) He is dead last among centers.

We will not lose hope! Randle's numbers defending the pick-and-roll are fine, per Second Spectrum. When Randle digs in, he can be a deterrent at the rim and (kinda) switch across all five positions. He is probably best suited as a switchable small-ball center, but building a roster in which he can play that role as a starter will be tough.

5. Luka Doncic, lost in space

The only thing that really matters from Doncic's sensational rookie season is Doncic proving he can already run a good offense. He is a passing savant with a jump shot and preternatural footwork.

He will become a decent defender, and perhaps even a very good one, as he gets in better shape. He's big and smart -- a good rebounder who already locks in during crunch time.

But in Year 2, Doncic needs to tighten up his off-ball work:

He has a tendency to get lost in no-man's land -- to turn his back on shooters, and dither into help position without actually helping anyone.

There is no point crashing the paint on the pick-and-roll if you do it late, at half-speed, and give the opposing big man a love tap:

Doncic's positional versatility has been more shield than sword on defense; it gives Dallas more flexibility hiding him on non-threatening players as if he's a late-career Lakers star.

Doncic will be fine on defense, and he's already a stud on the other end. Reminder: He gets to play with Kristaps Porzingis next season!

6. A good old-fashioned up-and-under

A little guy busting out a long-distance up-and-under is one of the coolest, most relatable NBA things:

Go to work, D.J. Augustin! That is a normal person driveway move. That is a move you use when you can't blow by anyone, and I say that from personal experience. (If the defender stays down, I'll need some help, please.)

Jayson Tatum isn't a little guy, but that just means he can traverse longer distances with a single pivot move:

(As a Tatum-related aside, I like this lineup for the Boston Celtics: Terry Rozier, Jaylen Brown, Gordon Hayward, Tatum and Aron Baynes/Daniel Theis. The Baynes version has killed it so far. The Celtics should never rest Tatum, Kyrie Irving and Al Horford at the same time. Such lineups don't have quite enough shooting. If Irving and Horford are on the bench, Tatum should be on the floor.)

We think of the up-and-under as a post move. Kevin McHale, of course, is the all-time master. It's fun to see perimeter guys improvise with it farther from the hoop.

7. It's just not happening for Marquese Chriss

Andrew Wiggins is the current captain of the "It's Just Not Happening" team, but Minnesota Timberwolves fans have been through enough.

Chriss has somehow regressed in Year 3, and playing real minutes with the Cleveland Cavaliers has made things worse. I'm not sure there is any player more out of sorts on offense. He's shooting 28 percent on 3-pointers and 46 percent on 2-pointers. His fouls and turnovers have spiked in the manner of someone who is still a beat behind processing the game.

The Suns eased Chriss into some playmaking duty from the elbows, and at times, he looked comfortable there. Not now. He commits illegal screens on handoffs, and throws passes that are too late or off-target:

He just runs into dudes in traffic:

Help defenders seem to surprise him. He doesn't have a Plan B. Perhaps most distressing: Chriss travels a lot -- in the post, when he tries to pump-and-drive, even just triggering run-of-the-mill dribble moves.

Chriss should be an NBA player. Let's hope he finds a stable path there.

8. Let's go easy on some of these technicals

Man, some of these refs have short fuses. On Sunday, Trae Young was tossed for staring down Kris Dunn after canning a triple. Nine days earlier in Atlanta, officials ejected Blake Griffin after two weak technicals -- the second of which came when Griffin yapped at the Hawks bench after drilling a sideline 3-pointer.

This season has featured quick-trigger technicals against Lance Stephenson for strumming his air guitar after a 3-pointer that put the Lakers up 32 points in Charlotte; and against Clint Capela for a very quick swing on the rim.

The Young and Stephenson techs show the lingering influence of the Malice at the Palace. The league understandably fears late-game taunting in blowouts -- the kind of rubbing-it-in-the-face that might infuriate a frustrated player on the trailing team. Ditto for staredowns between players who have already been warned about tense encounters -- as Young and Dunn were Sunday.

But can we chill a little with second technicals? The league is lucky Detroit rallied to win in Atlanta without Griffin. The Pistons are leading a semi-heated playoff race. Every game matters. Griffin is their best player. You can't eject him from a late-season game for talking trash.

9. Goodbye, Hack-a-Shaq

If we are going to needle refs for being against fun, we should also acknowledge that the league has eradicated Hack-a-Shaq. There have been only 33 intentional away-from-the-play fouls this season, putting the league on pace for about 45 such hacks -- down from 77 last season, 126 the year before, and an unwatchable 420 in 2015-16, per league figures released to ESPN.com.

After that season, the league extended the harsh late-game penalties for such fouls -- one free throw and the ball -- over the last two minutes of every quarter. Meanwhile, the league's two main Hack-a targets -- Andre Drummond and DeAndre Jordan -- have improved their free throw shooting to the point that the strategy no longer makes sense against them. Two other candidates -- Dwight Howard and Andre Roberson -- have been injured all or most of this season.

Lonzo Ball -- shooting a preposterous 41.7 percent on free throws -- is hurt, too. Downturns for D.J. Wilson (11-of-28), OG Anunoby (21-of-44) and Steven Adams (53 percent) are probably random. That leaves one guy to monitor: Hassan Whiteside, shooting 44 percent after hitting at least 60 percent in each of the past three seasons. If he stabilizes, we might be in the Hack-a-Shaq clear until Roberson returns.

Next up: banning the clotheslines and wrap-ups that abort fast breaks.

10. Aggressive court-wipers

This guy is either super-committed to his job, or a little reckless -- or both.

If D'Angelo Russell throws a bounce pass to Rodions Kurucs, our mopper -- belly-flopping into a double-towel breaststroke -- might accidentally intercept it. Our guy loves his area of the floor. He dotes on it like Kramer picking up trash along his highway mile. He will risk bodily harm to keep his territory pristine.

The best mopper-related drama happens when they venture farther onto the floor with actual mops during live action, and the offensive team coughs the ball up -- leading to a fast break coming right at the poor court-wipers. They have to pick up those mops and rush back to the baseline. You can see the terror in their eyes.

11. The subtle brilliance of Paul George

So much of good defense lives in the absence of anything happening. Witness these six seconds of nothing -- but everything -- from George:

He navigates a Nikola Jokic screen untouched, and then blocks the passing lane between Jokic and Malik Beasley. Jokic nudges past Steven Adams, but George lingers in the lane to stop him. Perhaps he has strayed too far, and stayed too long. Jokic pings the ball to Beasley in the corner. George is already moving there before the ball is out of Jokic's hands, and he's fast enough and long enough to get back to Beasley.

It can appear as if George is cavalier with shooters -- as if he has left them too open. But it's really that he knows exactly how much time his length and athleticism buy him, and how to exploit every millisecond of that time.

George closes out on Beasley without losing his balance, or flying by him. Beasley has nothing. Denver starts from scratch.

George will never challenge as many raw shot attempts as the big men jostling with him for Defensive Player of the Year. That is inherent in the positional differences between wings and bigs. But you wonder how much sequences like these define what kinds of shots those big men end up challenging -- who shoots them, from where, and under what level of pressure from both the defense and the shot clock.