NEW YORK -- Fifty years into the Open era and there are still plenty of hot-button issues.

Should men play best-of-three sets in majors? Why aren't final-set tiebreakers used in all events? Have rackets and strings and all the technological advances made the game too powerful?

We can debate these (and many more) for the next 50 years if we choose. But one discussion that has largely (but not completely as you can see here and here) been resolved in recent times is equal prize money between men and women.

It was a long time coming. The first real public plea came in Rome's storied Foro Italico in 1970, only two years into the Open era, when the winner of that event, Billie Jean King, called for equal distribution of winnings.

Ilie Nastase, the men's winner, took home $3,500, while King made a mere $600. The discontent had ramped up, and King would later offer these famous words: "Everyone thinks women should be thrilled when we get crumbs, and I want women to have the cake, the icing and the cherry on top, too."

As the years went on, the gap between earnings slowly closed, but in Grand Slam tennis, the final volley in the battle for equal prize money did not come until the spring of 2006 at the French Open.

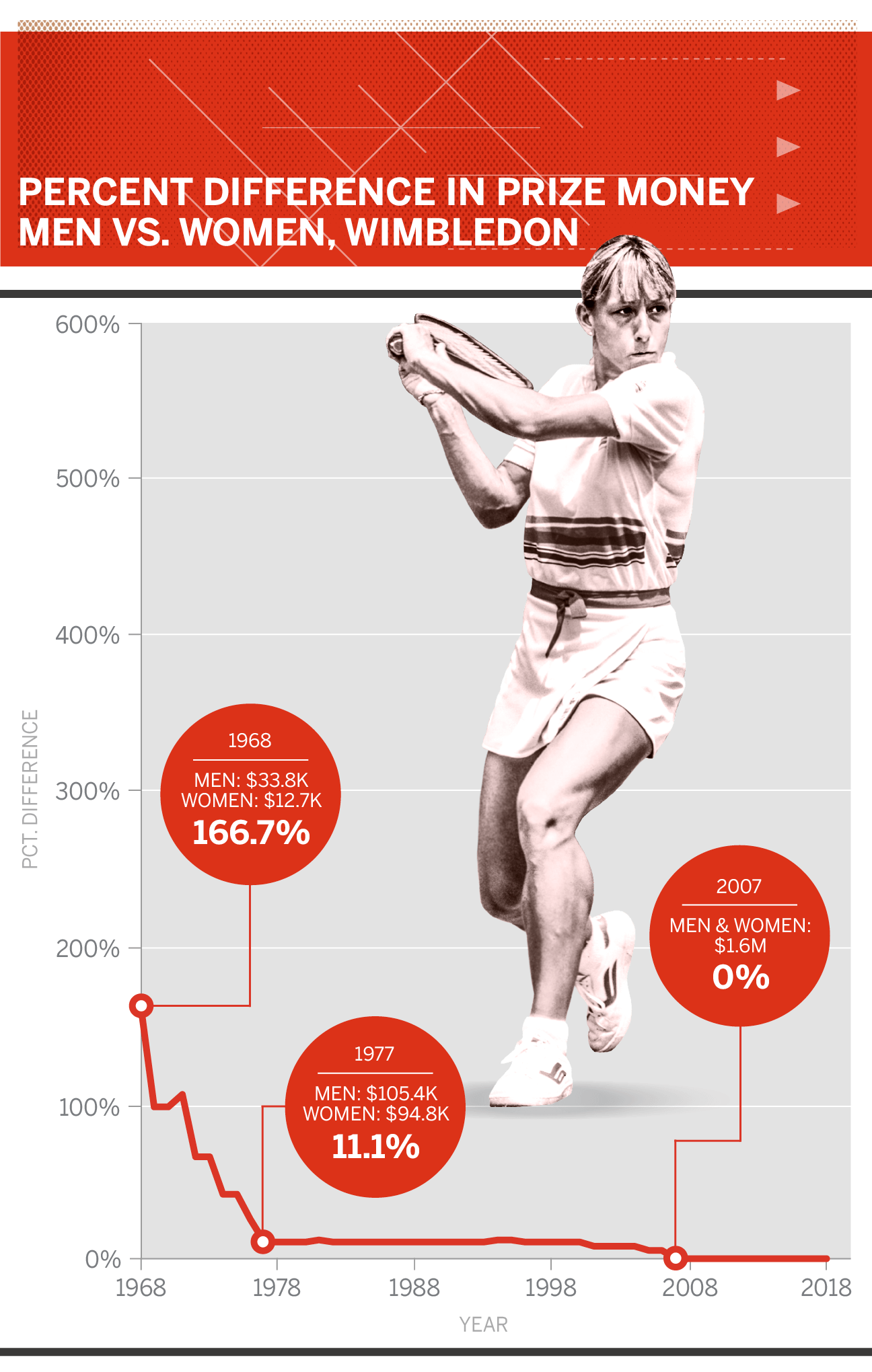

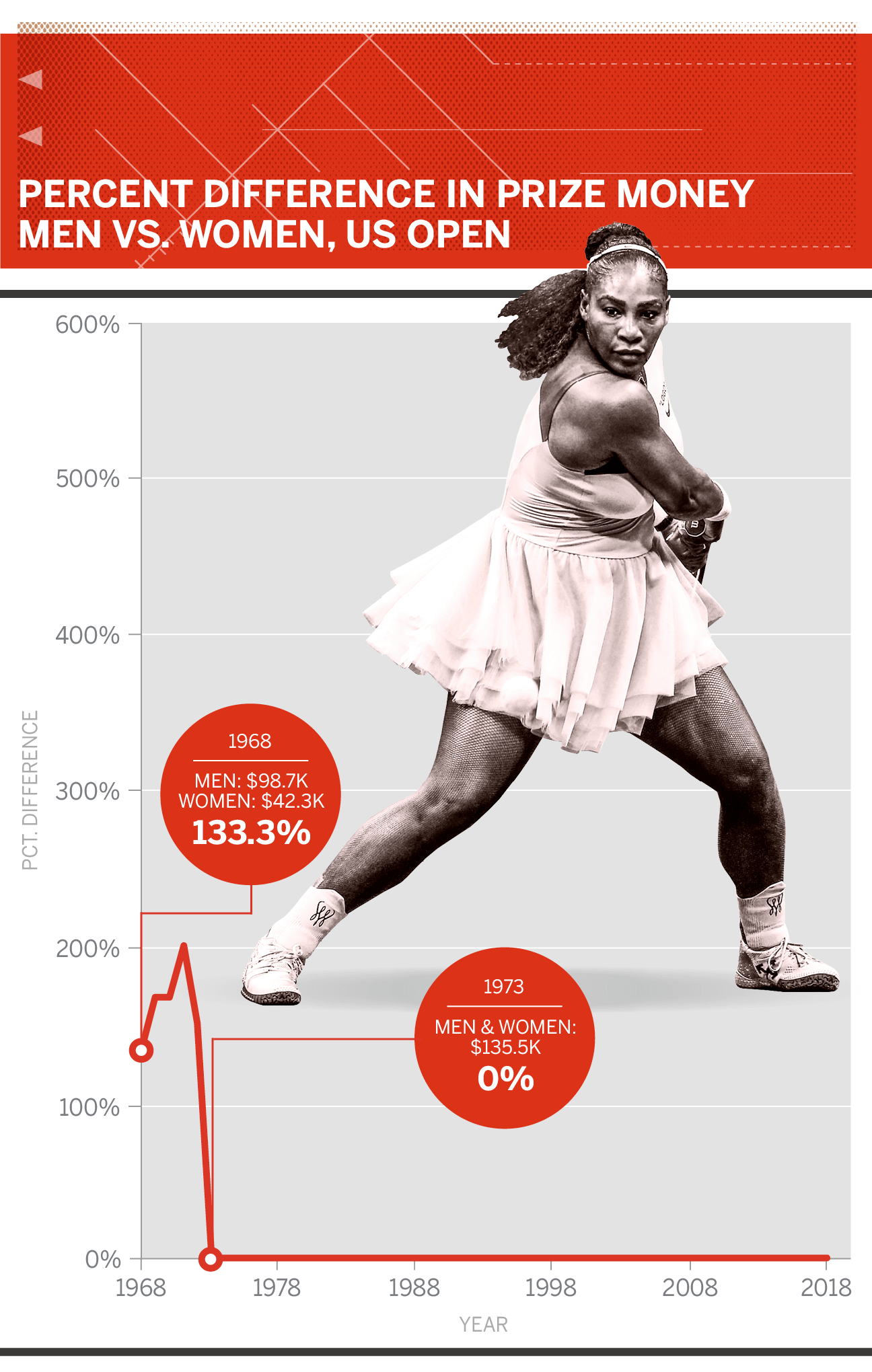

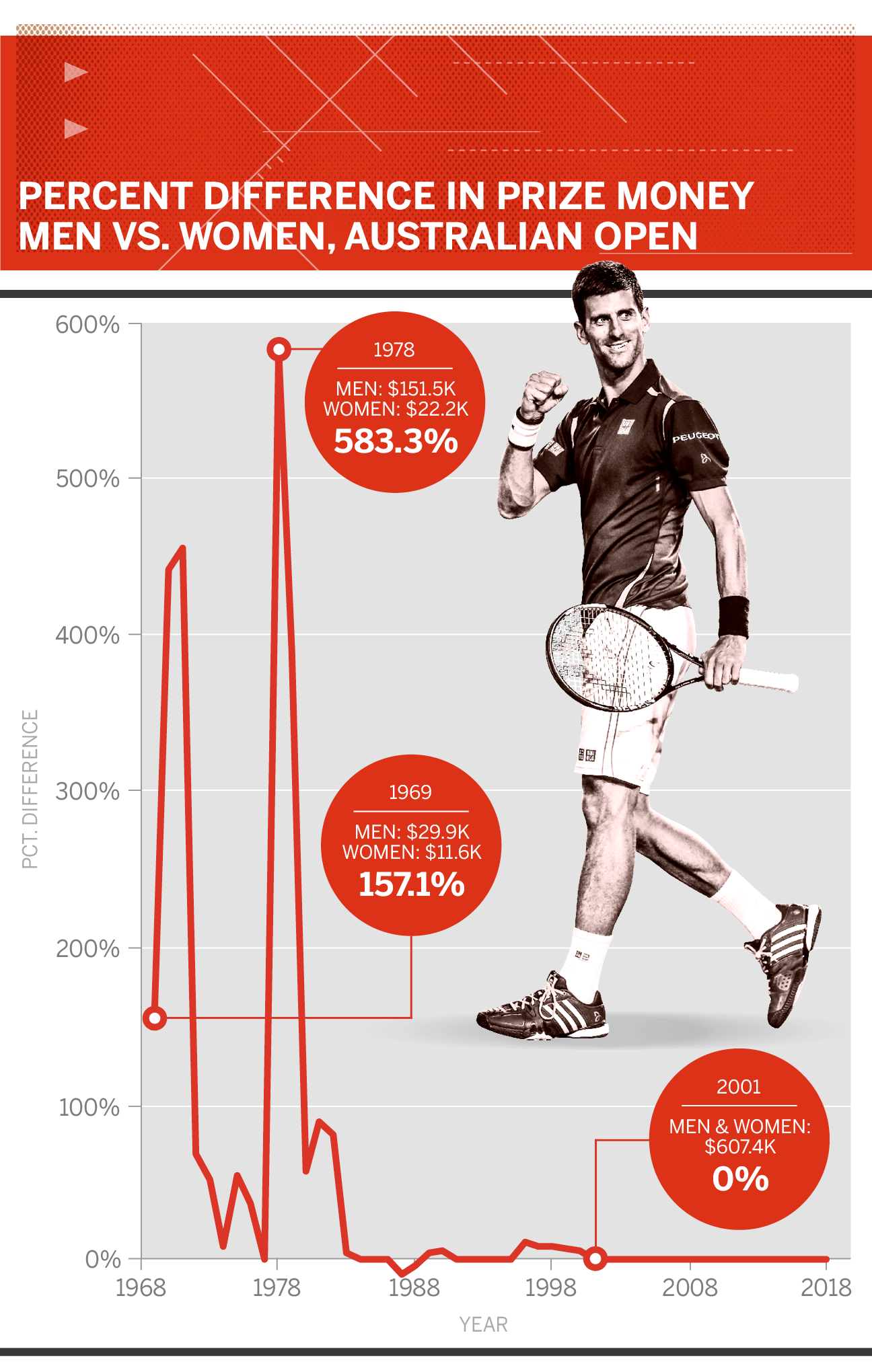

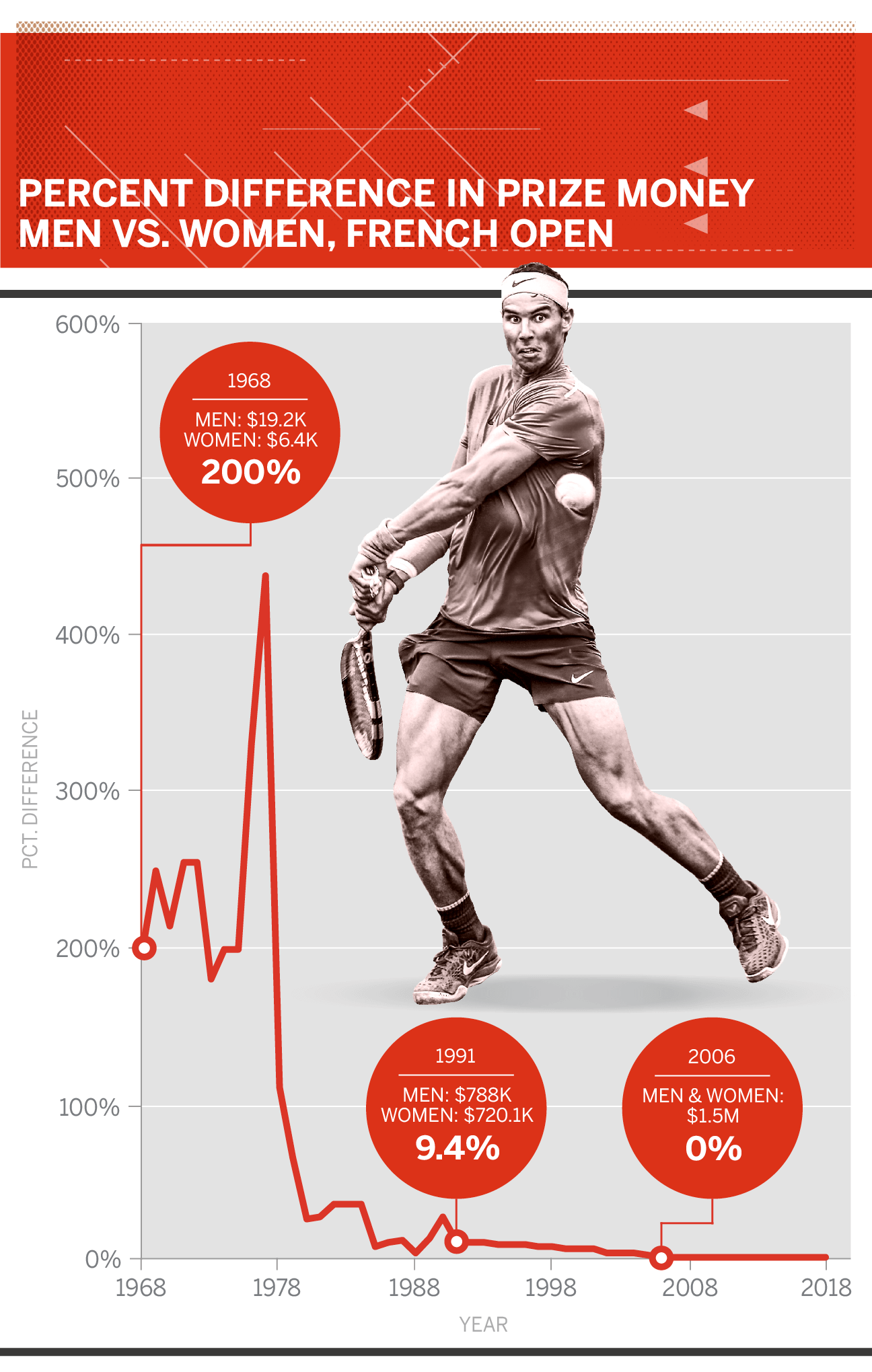

Below is a timeline showing how the four majors gradually moved toward today's state of parity, in the order the tournaments achieved it. The figures in the graphs show the difference in percentage of prize money between men and women since the start of the Open era.

US Open

The Italian Open was the flashpoint that triggered King to lobby aggressively for equal prize money, an effort that earned her valuable allies in the burgeoning feminist movement in the U.S., including Title IX and The Equal Rights Movement.

King threatened a boycott of the US Open in 1973. Sensitive to the winds of change, the USTA instituted equal prize money for the tournament that year, with the winners, John Newcombe and Margaret Court, each taking home $25,000. The first-round losers each made $400. By comparison, this year's winners will earn $3.8 million and the first-round losers walked away with $54,000.

Australian Open

The first major of the year had an equal prize money policy early in the Open era; in fact, there were times when the Australian championships paid the women more. But by the mid-1990s, the men again earned more. At that point, WTA officials and players began working diligently behind the scenes for equal pay, which officials Down Under finally agreed to for the 2001 event.

"I think it's great that the Australian Open has gone back to equal prize money," defending champion Lindsay Davenport said. "Women's tennis has certainly proven that it is worth it."

This year, Roger Federer and Caroline Wozniacki won the event, each pocketing $4 million in Aussie dollars.

French Open

The French Tennis Federation was under increasing pressure to offer equal prize money, and they crossed that bridge in 2006, the second of the three consecutive years that Justine Henin won the event.

One of the most outspoken activists who helped convince the FFT to see the light of equality was Amelie Mauresmo, who earned equal prize money when she won the Australian Open in 2006, but less than the male champion when she also bagged the Wimbledon title that same year.

"As a Frenchwoman, I'm happy and proud of the French Open organizers," Mauresmo said.

Wimbledon

By the time Wimbledon finally instituted equal prize money in 2007, the figures were so close that the disparity seemed perversely symbolic. In 2006, the discrepancy between male champion Roger Federer's check (655,000 pounds) and that of women's champ Mauresmo's check (625,000 pounds) was just 5 percent.

But Wimbledon did beat the French to another key reform when it declared, a month before the French did, that it would pay equal prize money each round (instead of just to the winners). Venus Williams was one of the most vocal activists for equality at Wimbledon.

In an interview and op-ed column, she kept the pressure on. Then her sister, Serena, won the first Wimbledon offering equal prize money.