The final stage of the Tour de France is often labelled ceremonial because the overall winner of the three-week race is determined the day before, but the annual battle on the famous avenue is the most prestigious showcase in the sport for fast-twitch sprinters. It's no cruise for the rest of the field, either. Stress levels are high, and the overall winner wants to stay out of trouble and cross the finish line upright.

"It's sort of like a party. You just roll into town all easy, but then everybody gets all crazy, and they start racing again. It's like you have finished the race, but then there's another race, and if you win this race, it's one of the most historic wins you could have in your entire career," said Taylor Phinney, the Coloradan who rides for EF Education First-Drapac.

We asked Fred "Fast Freddie" Rodriguez, a retired sprint specialist, to break down the course, the tactics and the ambiance of the finale. Rodriguez, a four-time U.S. road champion who won races in his own right, served as a leadout man for some of the top sprinters in the sport during a 20-year pro career. In the 2000 Tour de France, riding for the Mapei team, Rodriguez executed a successful leadout for Italy's Stefano Zanini to win the Stage 21 finale on the Champs-Elysées. He says the skills that come into play there are almost impossible to capture on camera.

The course

Teams with riders in the hunt for a stage win put fatigue aside in Paris and gear up for multiple circuits that take a slight uphill on the Champs-Elysées, circle the Arc de Triomphe, head down the other side of the avenue past a number of other landmarks, traverse a tunnel near the Louvre museum, skirt the obelisk on the Place de la Concorde and cross the finish line. They throttle up to full power in the last couple of laps to deliver their man to the finish line, jockeying for position on cobblestones that become treacherous when wet.

Distance: 116 km (72 miles)

Surface: Cobblestone, also known by the French term pavé, laid in an overlapping fan pattern.

"Sprints on pavé are not very common in the sport," Rodriguez said. "It's really hard to change your trajectory and speed once you're on it, so how you come onto it is how you end up. The bike's not gripping as well. You're bouncing all over the place. And there are so many corners. You're always fighting for position and making sure you or your teammates are with your sprinter. It's hit-and-miss to be in the right place at the right time the last couple corners."

Number of circuits: 8

Circuit length: 7 km (4.3 miles)

Finishing straightaway: 400 meters (0.25 miles)

Width of the course: 9 meters (30 feet)

"The width of the course makes it a pain for the sprinters because you always have people coming up," Rodriguez said. "There's continuous surging to stay at the front. If you're too far back on the U-turns, you're expending a lot of energy having to reaccelerate while the front is riding at a smoother pace. So even though it seems wasteful to ride toward the front, it's actually a smoother ride than at the middle or the back, where you're getting a slingshot effect."

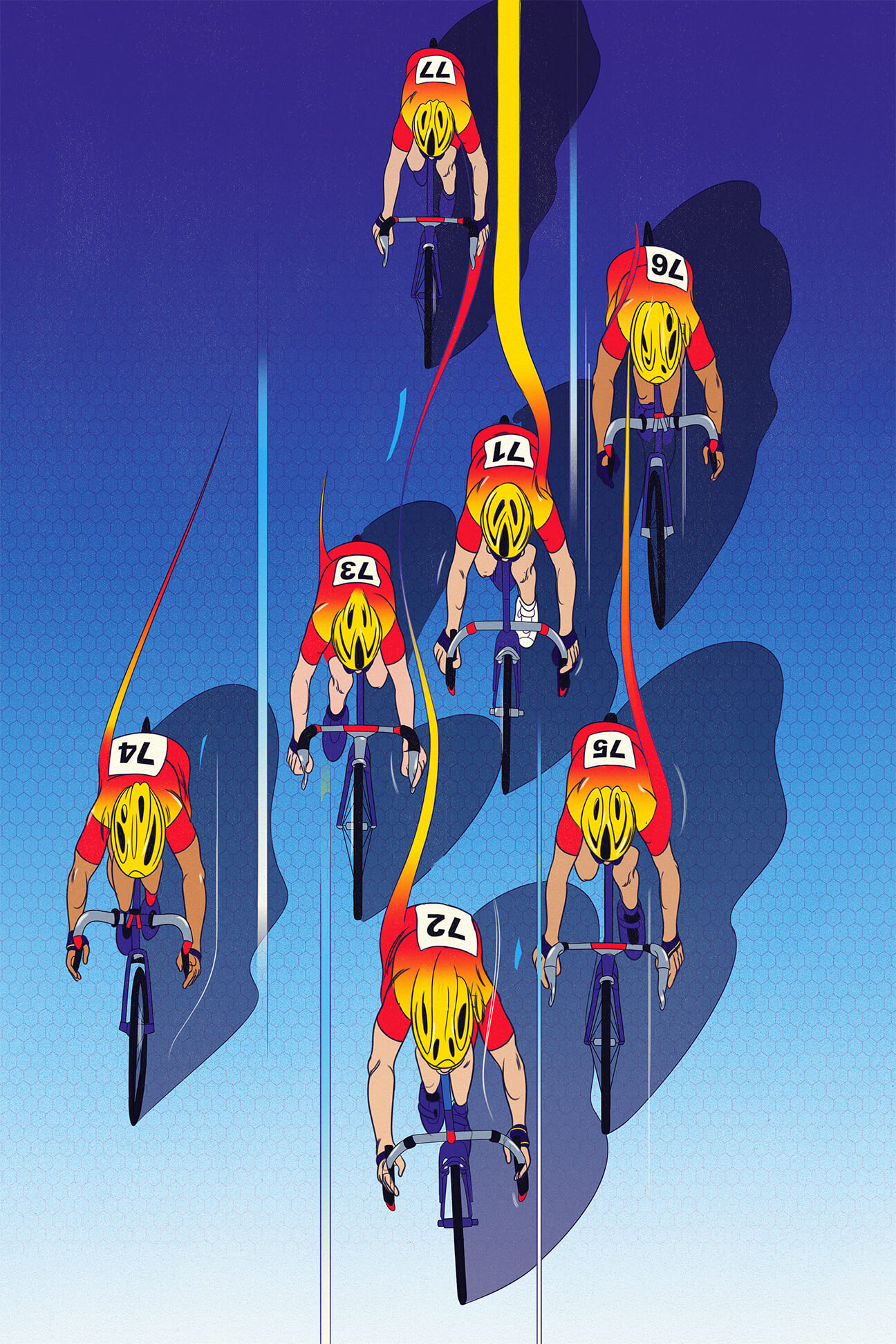

The train

Going into the last two circuits, teams that want to launch sprinters begin to form "trains,'' falling into single file and taking turns pulling at the front while keeping the sprinter protected from wind and jostling. Because it's the end of a grueling, three-week race, many teams don't have full trains, so they vary in number. But there's always one man whose job is to "lead out" the sprinter, pacing him to the spot he wants to be in the bunch or even putting him in position to hitch onto another team's train and then peeling off.

The team organizes its train, trying to stay parallel with other teams near the front.

Riders rotate, taking pulls of varying distances, depending on their form that day.

One or two riders make the last big push to get the sprinter into ideal position, generally on a top rival's wheel.

The leadout man peels off and gets out of the way, leaving the sprinter to surge in the last 200 to 400 meters.

"You come out of the tunnel, go uphill, make that left turn and fight to be in the spot you want to be," Rodriguez said. "The worst thing is you come out of tunnel and the leadout train dies, and you're stuck and get swarmed from 15 guys back. At the right turn, you give it your last little effort and get out of the way so the sprinter can follow (another) train. It's a beautiful art. The bummer is it's so hard to show the fans how much is going on. The aerial shots do, but there's not enough of it to get the full gist of what's going on with the leadouts. You'd have to replay it over and over again to show the intricate details of who got stuck at the wrong time.''

The bike throw

When riders contesting a sprint anticipate that there will be a photo finish, they will often do a "bike throw,'' driving the handlebars forward so that their front wheel leaps out just enough to gain a slight advantage.

"It's an intuitive learning thing you do, like a kid dribbling a ball," Rodriguez said. "You're leaning far forward over your bike, over the top of your bars. There's a split second you can make up about half a wheel. You're throwing your bike with the last little bit of stretch, and before the bike gets away from you, you grab it. You're so in the moment, and sometimes you don't fire at the right time. Time it perfectly to the line, and it can be the difference between winning and losing. I've seen riders do it so passionately and so hard that they lose control of the bike."

The green jersey

While the Tour's green jersey is often thought of as the sprinter's jersey, it goes to the winner of a race-within-the-race for points gained in intermediate sprints and stage wins. It is sometimes won by a pure sprinter but more often by riders who can handle hilly terrain and seize opportunities in some non-sprint stages.

Slovakia's Peter Sagan clinched his record-tying sixth green jersey in Stage 16 of this year's Tour. Two days before, in Stage 15, he became the first rider to hit career triple digits in the number of days wearing a specialty jersey. He has never won the sprint on the Champs-Elysées, and with several specialists out of the race, don't be surprised to see him go for it.

Jens Voigt of Germany, who spent 17 years in the pro peloton and was known for his penchant for breakaways, calls Sagan "the Beethoven of cycling, the Einstein of cycling."

"The green jersey is not for the best sprinter. It is for the hardest working sprinter, a sprinter who gets points at any possible occasion. And that is simply Peter in this decade," Voigt said. "There is no way around him. He can be with the best on a totally flat and fast stage where pure speed is needed, and he can also win on short, uphill finishes and even in the medium-range mountains. Another strength is his flexibility. If he gets the perfect leadout train, he is happy and wins. If his leadout is messed up, he simply shrugs his shoulders and follows the next-best sprinter and wins. It must be very frustrating to race against him, being shown that you probably never will reach his level."

1,417 watts: Sagan's peak power during an 18-second sprint at the 2017 Tour de Suisse, which could have powered a television for more than 20 hours.

Additional reporting by Dan Hajducky. Illustrations by Andrew Archer.